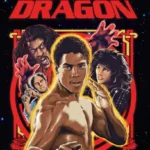

Few cult movies have aged as strangely, loudly, or lovingly as The Last Dragon. Released in 1985 at the height of Reagan-era pop excess, the film feels like it was beamed in from an alternate universe where kung fu philosophy, MTV aesthetics, blaxploitation swagger, and Saturday-morning sincerity all coexist without irony. Directed by Michael Schultz and produced by Berry Gordy, The Last Dragon is not just a martial arts movie or a music movie or a comedy—it’s all of them at once, wrapped in neon, synths, and unshakable belief in its own weirdness.

Few cult movies have aged as strangely, loudly, or lovingly as The Last Dragon. Released in 1985 at the height of Reagan-era pop excess, the film feels like it was beamed in from an alternate universe where kung fu philosophy, MTV aesthetics, blaxploitation swagger, and Saturday-morning sincerity all coexist without irony. Directed by Michael Schultz and produced by Berry Gordy, The Last Dragon is not just a martial arts movie or a music movie or a comedy—it’s all of them at once, wrapped in neon, synths, and unshakable belief in its own weirdness.

At its core, The Last Dragon tells the story of Leroy Green, a young martial artist from Harlem whose life is devoted to mastering kung fu and achieving the final level of enlightenment known as “The Glow.” Leroy is not interested in money, fame, or romance. He’s obsessed with discipline, humility, and honor, living by the teachings of his master even as the world around him mocks his seriousness. Taimak, a real-life martial artist with no prior acting experience, plays Leroy with a wide-eyed earnestness that becomes the film’s emotional anchor. He’s not cool in the traditional sense, but his sincerity is exactly what makes the character work.

The film’s Harlem setting is crucial. This is not the gritty, crime-ridden Harlem often depicted in 1980s cinema, but a vibrant, hyper-stylized version full of color, music, and personality. Street corners pulse with sound, arcades glow with artificial light, and martial arts schools exist alongside movie theaters playing Bruce Lee films on a loop. The Last Dragon celebrates Black urban culture while simultaneously paying deep respect to Asian martial arts traditions, creating a cultural mashup that feels both naive and strangely progressive for its time.

Opposing Leroy is one of the great villains of 1980s cinema: Sho’nuff, the self-proclaimed Shogun of Harlem. Played by Julius Carry with scene-stealing intensity, Sho’nuff is pure theatrical excess. Dressed in red leather, dripping with chains, and surrounded by his own gang of devoted followers, Sho’nuff is loud, aggressive, and desperate for validation. He wants to be recognized as the greatest martial artist alive, and Leroy’s quiet discipline drives him insane. Every time Sho’nuff appears onscreen, the movie kicks into a higher gear, fueled by Carry’s booming voice and exaggerated bravado.

Sho’nuff isn’t just a villain—he’s a parody of toxic masculinity, ego, and performative toughness. His obsession with recognition contrasts sharply with Leroy’s internal journey. Where Sho’nuff demands respect, Leroy earns it without asking. This thematic tension gives the film more depth than it often gets credit for, grounding its silliness in a genuine philosophical conflict.

Adding another layer to the film is Vanity’s performance as Laura Charles, a music video VJ trying to keep her struggling show alive in a cutthroat entertainment industry. Laura is not a passive love interest. She’s ambitious, sharp-tongued, and fiercely independent, navigating a world that underestimates her while still finding space for vulnerability. Her chemistry with Taimak is unconventional but charming, built more on mutual respect and awkward sincerity than traditional romance.

Music plays a massive role in The Last Dragon, both narratively and culturally. The soundtrack is a time capsule of mid-1980s R&B and pop, featuring artists like DeBarge, Stevie Wonder, and Vanity herself. The title song, “The Last Dragon,” embodies the film’s tone perfectly—earnest, inspirational, and unapologetically of its era. The music doesn’t just accompany the story; it defines the world, reinforcing the film’s fusion of martial arts mysticism and pop culture excess.

Visually, The Last Dragon is a feast of neon lights, smoke machines, and bold production design. It looks like an extended music video, which makes sense given Berry Gordy’s involvement and the film’s deep ties to Motown aesthetics. Every frame feels carefully stylized, sometimes to the point of absurdity, but that excess is part of the charm. The climactic “Glow” effect—Leroy literally illuminating with golden energy—is both ridiculous and strangely triumphant, a visual metaphor for self-realization rendered with 1980s special effects bravado.

Critically, The Last Dragon was not universally embraced upon release. Some dismissed it as too goofy, too campy, or too unfocused. But over time, the film has been reclaimed as a cult classic, appreciated for exactly the qualities that once made it easy to mock. Its sincerity, its refusal to wink at the audience, and its wholehearted embrace of genre blending feel refreshing in retrospect. The movie never apologizes for itself, and that confidence has allowed it to endure.

The film’s legacy can be felt across music, fashion, and pop culture. References to Sho’nuff appear in hip-hop lyrics and music videos. The Glow has become shorthand for personal empowerment. Artists like RZA, Janelle Monáe, and Chance the Rapper have cited The Last Dragon as an influence, drawn to its unapologetic celebration of individuality and spiritual growth within a pop framework.

What truly sets The Last Dragon apart is its message. Beneath the flashy visuals and quotable dialogue is a story about self-mastery and integrity. Leroy’s journey isn’t about defeating others—it’s about defeating doubt, fear, and ego. The final confrontation doesn’t just resolve a physical conflict; it represents the culmination of internal growth. The Glow is not bestowed by an external master but unlocked from within, a surprisingly profound idea wrapped in a crowd-pleasing finale.

In an era where irony dominates and nostalgia is often filtered through cynicism, The Last Dragon stands as a reminder of what happens when a film commits fully to its vision, no matter how strange that vision might be. It’s a movie that believes in honor, love, discipline, and the power of being unapologetically yourself. That belief radiates through every awkward line reading, every synth-heavy cue, and every glowing fist.

Nearly four decades later, The Last Dragon remains endlessly watchable—not because it’s perfect, but because it’s fearless. It takes big swings, embraces its contradictions, and invites the audience to do the same. In the process, it achieves something rare: a cult classic that feels timeless not despite its flaws, but because of them.

…. Stream For Free On Tubi

This post has already been read 294 times!