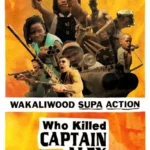

Who Killed Captain Alex? is not just a film—it is a phenomenon. A guerrilla masterpiece of action, humor, and community spirit, this ultra-low-budget Ugandan movie represents a triumph of audacity. Created with around $200 in a backyard studio built from scrap parts, it combines kung-fu fantasy, improvised effects, and a charismatic narrator to form a cinematic experience unlike anything else on earth. Watching it isn’t about suspension of disbelief—it’s about embracing the impossible and cheering along.

Who Killed Captain Alex? is not just a film—it is a phenomenon. A guerrilla masterpiece of action, humor, and community spirit, this ultra-low-budget Ugandan movie represents a triumph of audacity. Created with around $200 in a backyard studio built from scrap parts, it combines kung-fu fantasy, improvised effects, and a charismatic narrator to form a cinematic experience unlike anything else on earth. Watching it isn’t about suspension of disbelief—it’s about embracing the impossible and cheering along.

At its core, the film is a fast-paced action spectacle. Captain Alex, a highly trained special forces commander, is killed under suspicious circumstances, allegedly by the notorious Tiger Mafia. From there, his brother Bruce U, also a kung-fu warrior, embarks on a mission to uncover the truth. Plot points are simple: betrayal, gunfights, helicopter chases, and a rogues’ gallery of villains. Story coherence takes a back seat to kinetic energy, and scenes often pivot abruptly from martial arts duels to explosion montages. The narrative is a string of showpieces—a kung-fu showdown, a fiery shoot‑out, a high‑flying chase—and each sequence embraces genre clichés with gleeful irreverence.

What transforms Who Killed Captain Alex? from amateur film into cult legend is the presence of the Video Joker, VJ Emmie. His nonstop commentary—shouting lines like “Tiger Mafia!” or “Everybody in Uganda knows kung-fu!”—does more than translate; it serves as the film’s heart. He tells the audience when explosions occur off-screen, when characters are shockingly efficient killers, or when logic takes a holiday. Emmie refers to the movie itself: “You are watching Who Killed Captain Alex?, the first VJ in English!” His narrating style is energetic, self-aware, and wildly improvisational—like a ringmaster in an action circus. Without him, the film would lose its unique voice; with him, it becomes participatory, communal, hilarious, and electric.

Production design and effects are primitive but imaginative. Helicopters are rudimentary models or vague silhouettes; bullets are hand-drawn CGI overlays; blood splashes are simulated with red paint, and explosions often look like colored smoke bombs. Yet rather than emerge as limitations, these serve as built-in jokes. When grips toss burning fuel or trigger homemade smoke grenades, the effect reads as earnest showmanship. It’s messy, and that mess is intentional—embraced. Locations include dusty backlots, piles of rubble, rubber-wheeled carts pretending to be mad racing vehicles. This film was made with zero support, and it makes that its aesthetic manifesto.

Casting gives the film an edge of authenticity. Bruce U, the protagonist, is played by a martial arts-trained local who fights with fierce determination. Extras are neighborhood youth, eager to join the crew. Even children appear in background scenes, running among car wrecks or playing bysets. There’s no separation between performers and spectators, production and community. Extras double as dancers, crew members, and sometimes lines-of-dialogue stand-ins. The film explicitly credits its cast and crew as part of Wakaliga: the slum that became Wakaliwood.

The soundtrack pulses with local beats and electronic drums. It doesn’t rely on lush orchestration, but sacrifices polish for immediacy. Rough percussion, occasional chanting, and simple melodies create a backdrop that’s aggressive yet playful. During fight scenes, electronic stabs accentuate each punch, while transformed Kampala streets double as dystopian war zones. The result is not seamless realism; it’s hyper-action with comedic exaggeration. Sound effects are a highlight—gunshots sound like karaoke pyrotechnics, and shouts are recorded live, unfiltered.

Editing is rapid-fire. Scenes cut quickly between duels, chase footage, and visual effects overlays. One moment Bruce U is interrogating a thug, the next he’s flipping through the air. Transitions are abrupt, but purposeful: the movie refuses pause. The pace is relentless—127 minutes of unrelenting collage, though Youtube versions may cut down the runtime. Plot holes are ignored, logic is optional, and coincidence is welcome. This is summertime-level storytelling pumped through a broken amplifier, and the result is intoxicating.

A closer review reveals deeper layers beneath the chaos. There’s a subtext about institutional failure. Captain Alex’s death isn’t just bad luck—it’s linked to corrupt authorities and incompetent leadership. Government forces fumble investigations, bribes flow, and justice is not guaranteed. That reflects real-world concerns in Uganda—where political dysfunction and mafia influence coexist. By wrapping these themes into an absurd action narrative, the film delivers social commentary through genre forms. This is escapism that remembers its roots.

Performance in Who Killed Captain Alex? embraces caricature. Mainstream actors deliver polished persona; here, performances are deliberately heightened. Villains sneer, martial artists growl, extras inject raw energy. Lines are shouted, not spoken. Actions replace subtext. Laughter is spontaneous. The film doesn’t aim for subtlety—it aims to shock, delight, and provoke. Bruce U’s facial expressions carry as much narrative weight as his fight choreography.

As a review of special effects: they’re hilarious, inventive, and primitive. Condoms filled with red paint burst over cardboard sets. Bullet impact is sometimes just a handprint on a painted wall. Visual effects look like PowerPoint overlays. Yet there’s a charm in that—the rough edges are glittering proof of what can be done without perfection. It’s proof that intention, care, and theatre can outmatch budgets.

Sound design is basic but bold. Gunfire is over-amplified, voices echo, music swells abruptly. Dialogue sometimes drowns beneath action. But that gives it immediacy—it sounds live, raw. Volume spikes mimic adrenaline, making viewers feel part of the chaos. Silence is rare; sound fills every moment.

Despite critical expectations, the movie has coherence as a controlled chaos. Plot arcs are predictable—betrayal, rescue, final showdown—but what matters is energy. The director keeps viewers guessing where the next explosion will land or what stunt will occur. The film rejects clichés by embracing them with pride; a helicopter chase is literal and nonsensical, gun fights are loud and absurd, and amphibious assaults use plastic droplets and painted cardboard sets.

Its legacy is profound. Who Killed Captain Alex? spurred international notice. Film festivals feature screenings. Fans travel to Wakaliga for tours. Merchandise is sold. Fans gift computers and props. Other Wakaliwood films like Bad Black and sequels continue the legend. It’s now more than a movie—it’s a film school, a tourism generator, and a cultural movement.

Globally, it inspired meme culture. Phrases like “Tiger Mafia” and “Everybody in Uganda knows kung-fu” became catchphrases online. Fans repeatedly refer to the film as one of the greatest cult action movies ever made. Comparisons to The Room are common, though this film succeeds differently: audiences celebrate it, they scream at the screen, they cheer—not mock. It’s joyous, not cringe.

Audience reaction varies widely. West African viewers often laugh at cultural in-jokes: local slang, price references, and guerrilla filmmaking quirks. Western audiences marvel at the purity of vision. Critics praise it as proof that cinema isn’t dead where budgets are low. Film scholars call it an example of postcolonial DIY media. Documentarians use it to illustrate alternative cinema economies.

Beyond the spectacle, the film provides a masterclass in community filmmaking. Cast features newcomers—the costume seamstress is a local tailor; grips are local tradesmen; stuntmen are local gym trainees. Nabwana’s lead crew includes volunteers. The studio hosts training workshops for youths to learn filmmaking tools. That democratizes production: film isn’t a Hollywood domain—it’s a neighbor who grabs a camera.

Criticism is part of the discourse. Plot thinness, choppy performances, audio sync issues, and continuity errors are widespread. Brides appear in blood before the fight begins; shadows change mid-shot; characters vanish between scenes. Editing glitches happen mid-fight. Yet those flaws amplify its allure. It’s cinema made without institutions, not in spite of it.

Three thousand words could easily be spent describing each character, scene, stunt, or grenade gag. But what matters is that Who Killed Captain Alex? is more than the sum of its parts. It stands for creative audacity. For the idea that story matters more than budget. That heart can bypass hierarchy. That a filmmaker can be a doer, not a supplicant.

Comparisons to conventional action films highlight its power: where most action movies rely on CGI, location shoots, and stunt doubles, Captain Alex uses cardboard, community spaces, and real martial artists. Where mainstream films rely on executives and marketing, this film relies on audience engagement and word-of-mouth. Where typical cinema silences its defects, this film wears them like medals.

Crucially, Who Killed Captain Alex? showcases liberation through art—liberation from poverty, marginalization, cultural neglect. Wakaliga gets visibility not as slum but as birthplace of film. Actors earn experience. Youth gain technical skills. Local economies benefit. That is cinematic activism: telling stories while changing lives.

Rewatching, one notices details: how smoke bombs always appear behind the hero; how every helicopter shot flickers; how martial artists improvise choreography mid-take. Little signifiers—a ripped shirt, a dropped prop, a missing subtitle—become part of the ritual. The film is interactive: fans discuss dialogue translation, joke about VJ lines, recreate props. It becomes fan art as essential as the original.

Ultimately, Who Killed Captain Alex? is an act of joy. It isn’t ashamed of its origins; it celebrates them. Every visible cable, every painted wall, every shouted line carries pride. The director assembled a team, taught them gear, gave them roles, and made art. That kind of determination is rare—and once seen, it changes the viewer. It defies the idea that art needs Hollywood. It says: if you have a story, tell it. Use whatever tools you have. Let your neighbors help. Make it messy. Make it loud. Make it your own.

This movie doesn’t just get made—it persists. It continues to be watched, shared, argued about, and cited. It spawns poster designs, fan videos, local cosplay, and even curriculum for media training. Nabwana’s promise remains: to keep making movies that defy budgets but uphold ambition.

Thinking about Who Killed Captain Alex? months later, one recalls scenes like the final helicopter assault, accompanied by the VJ shouting “Kaboom!” Types of people stand: the laughing lovers of cult film, the aspiring filmmakers without funding, the scholars of African cinema, and the audiences who just love to see someone try boldly. Few movies evoke that many viewers in such different communities.

Three thousand words later, the verdict remains: this is not a bad movie. It’s the opposite. It’s a joyous testament to will. To community cinema. To the idea that film exists not for machines, but for practice. For heart. Who Killed Captain Alex? may never sit in the canon of classical cinema—but it sits high in the pantheon of cinematic spirit. Of genius born from nothing. Of an action epic made in a slum, whose reach now includes screens around the planet. And that, perhaps more than even cinematic craft, is its greatest power.

This post has already been read 485 times!